Loose Threads

We’re in the thick of summer movie photo calls now, and I have to ask: How are we feeling about Brad Pitt’s F1 fashion? He’s been out and about wearing shiny fabrics (pants and shirts), tie dye (also pants and shirt), and a jumpsuit (pants and shirt in one). He’s been accused of “unleash[ing] his inner fashion guy” (Harper’s Bazaar), “let[ting] his inner Tyler Durden come out to play in NYC” (GQ), and having a “midlife crisis wardrobe” (Times UK). So, dear Back Row friends: which one is it?

Elsewhere in photo call land, Scarlett Johansson has been looking incredible promoting Jurassic World Rebirth. I thought the pink Vivienne Westwood dress was so, so excellent — it’s a shame she has to pose with all this tacky dinosaur stuff! I appreciate that she’s not going full Twister and just showing up in brown.

I’ve been poking around the e.l.f. cosmetics site since it acquired Rhode. I hear good things about this skin tint with mineral spf 50 that promises no white cast. These adorable pink puffs ($6 for three) look perfect for letting a makeup-curious kid pretend like they’re putting on makeup.

If you’re an elder millennial looking to change up your sock game, I’m newly in love with these cute retro striped ones by Bombas.

Sophie Gilbert had a great piece in The Atlantic about how money is ruining television, writing, “The point of [And Just Like That] is no longer what happens, because nothing does. The point is to set up a series of visual tableaus showcasing all the things money can buy, as though the show were an animated special issue of Vogue or Architectural Digest.”

And now, onto today’s big story…

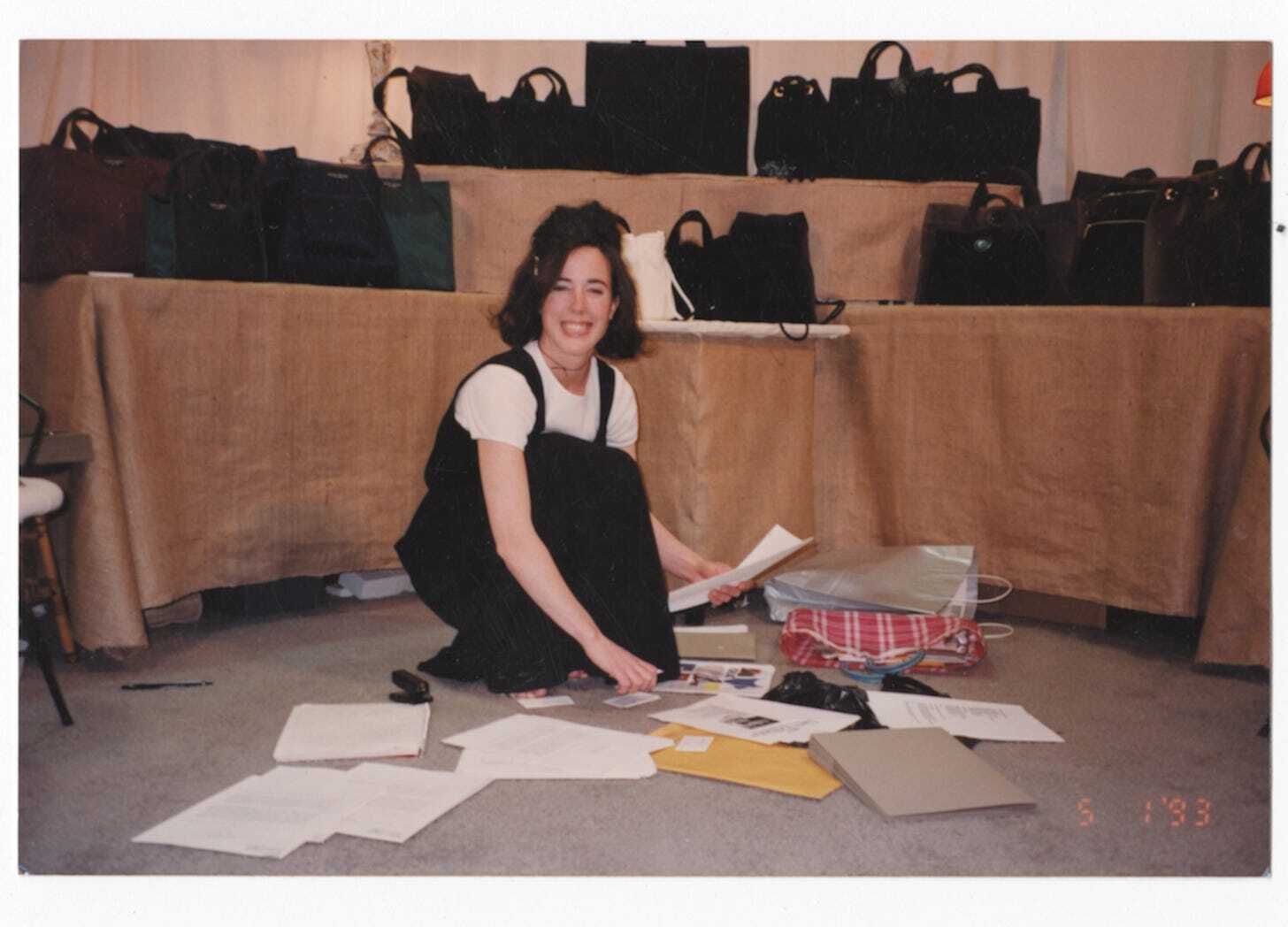

The Untold Story of Kate Spade

Kate Spade’s death at age 55 from suicide stunned the public when the news broke in the middle of 2018. It was just as shocking to her closest friend of 37 years, Elyce Arons, with whom she had founded two businesses, Kate Spade and Frances Valentine. Elyce knew that Kate, whom she calls Katy, was depressed, but still, “The whole thing was a huge shock to all of us,” she told me in a recent interview. “I was on the phone the day before with her. We were looking at houses in Napa. She was going to spend the summer there, and we’d started looking at real estate online, and I was texting her photos, and she was excited. So I don't know what happened.”

But the hard times are not the focus of her new book We Might Just Make It After All: My Best Friendship with Kate Spade, a propulsive account of co-founding one of the most iconic fashion brands of the nineties alongside Katy and her future husband Andy Spade, and entrepreneur Pamela Bell.

Elyce met Katy Brosnahan when they arrived at the University of Kansas as freshmen in 1981. They became close and transferred to Arizona State University, where Katy met Andy. Katy, Elyce, and Andy all ended up in New York together after graduating. After working five years in the accessories department at Condé Nast-owned Mademoiselle (where Elyce eventually got a job, too), Katy left in 1991 to take a stab at launching her own line at Andy’s encouragement. They decided to call the brand Kate Spade, and affixed a small black-and-white label to the outside of handbag prototypes that read “kate spade new york.” They agreed to an equity split of 30 percent for Katy and Andy, and 20 percent each for Elyce and Pamela.

The company became a huge success, selling a majority stake to Neiman Marcus in 1999 for $33.6 million before being bought outright by Liz Claiborne around eight years after that for $124 million. I talked to Elyce about the book and the story of Kate Spade, both the brand and the person.

Was Katy stylish from the day you first met?

She was very preppy when I first met her. It was a couple years after Animal House had come out, and everything at college — especially at K.U. — was really preppy. She was from Kansas City, which is cosmopolitan but conservative.

We were very, very different. My sister moved up to New York for ballet, and my mom brought me up several times. I had all of the trendy stuff I bought on Eighth Street that I thought was really cool. Everybody else probably thought I was a freak. I became a little bit more wanting to fit in at college. Hopefully I opened her eyes up a little bit to some of the trends going on outside. But she always had great taste.

Did she know in college she was interested in fashion?

We both loved it, but it didn't seem like a career choice for either of us at the time. She worked at a men's clothing store, and we were sort of like, maybe we could open a vintage shop — we talked about that. But of course, after we graduated from college, we had no money. I moved to New York. I thought, I'll get a job at a magazine or a newspaper. And when I got here, I had no connections, I just started temping.

Then Katy came [after a trip to Europe], and she was really upset that she couldn't get back to Arizona. I was like, just stay here, make some money, and then you can decide whether you want to go back or not. She's like, I don't know where I'm going to work. And I said, go to this temp agency Career Blazers, because my friend had told me that Condé Nast hires from them. They were sending me to Visa, Citibank. Of course, Katy’s first day she gets sent to Mademoiselle. I was like, This isn't fair. But I was happy for her.

Talk about Mademoiselle and what Katy’s job there was like.

If I had to liken it to a magazine today — Marie Claire. It felt French, like the twenty-something woman who was just getting her first job. There were really great editors there, stylists. They seemed so glamorous to me as a kid from Kansas. It was a really cool place to be, but also grueling. They worked really long hours, and then you had to go on a shoot at the end of it.

Katie was an assistant and then promoted to accessories editor, and she would go out into the market and she'd find sunglasses, belts, scarves. She'd do jewelry, she'd do handbags. It was a lot to cover. There was a separate shoe editor, so she didn't have to do that. She made a lot of friends with different designers and companies that made accessories.

So when you set out to start Kate Spade in the early nineties, what gap did you all see in the market?

I have to give all the credit to Katy for the whole concept, but also to Andy Spade who pushed her into doing it because she never would've done it. She didn't necessarily want to stay in magazines because she had risen to the top of where she wanted to be at Mademoiselle as a fashion editor. And she said the next step is management, which I don't want to do. So that's why she left. She said, “I'm not a handbag designer.” And Andy said, ”But you know what you like and what is missing out there that you couldn't find and you’d come home and talk to me about it all the time.”

She had these ideas of exactly what she wanted. I remember she sat in her apartment and cut out craft paper and taped 'em together with Scotch Tape. And then she took it to a pattern maker and they made a pattern and found a sample maker and had samples made.

What distinguished the bags aesthetically at that time?

There was no hardware. There was no luxury python or croc or anything über-luxurious about them. Yet they felt elevated because of the materials we used. The most popular was the really beautiful satin nylon we used. It was more of an industrial fabric. I think they also used it for furnishings.

What was the industry’s reaction to an editor going out and doing her own line?

I think everybody was really happy for her and supportive, and they wanted to cover the bags in the magazines. Vogue covered our raffia bags almost immediately, then they did a big feature on the four of us.

Did that coverage drive sales at the time?

Yes, absolutely. You would cut your page out of the magazine and put it up at a trade show [where stores were placing bag orders] to say, Vogue shot us.

When I was reading about how the four of you started the brand by going to the Garment District and finding suppliers, it sounded really quaint by modern manufacturing standards. Do you view it that way?

Yes. It was really hard. You had to go to all the fabric appointments — we still go to them because you have to touch and feel the fabrics before you buy them, look at the color saturation and the details. That part's relatively the same, and everything else is so different. Everything is accessible. You want to find a pattern maker, you Google it. But back then, they weren't really in the Yellow Pages. You had to ask industry people. We did have a few contractors who were not good and went out of business and almost closed up without us getting our stuff out of there. You didn’t know who's good and who's bad unless you get a recommendation. Today, we can manufacture anywhere else in the world and send them the spec sheets just through email.

Right — few brands probably start now by pounding the pavement in the Garment District.

Sadly, there's not much manufacturing [in New York] anymore. We had about five different factories at our height in New York City, when we were making everything here. Once we got bigger and we started hiring more senior production folks, they kept twisting our arms, like, “You’ve got to get out of New York. You're going to get much better quality, much better prices in these other factories in Asia.” So we did some sample runs there, and they were really good, and the labor was so much less than what we were paying here in New York City. And eventually all of our suppliers closed down here.

Neiman Marcus bought 56% of the company in 1999 for $33.6 million. How did you decide to sell to them?

Our attorney was working on a deal with them for something else. They said, we're interested in investing in about five different brands that are doing well at Neiman Marcus and growing them. They were the best store in the world to us. They had high standards, they carried beautiful designs. We met with the family. We really liked them, and we thought, This could be a really interesting partnership.

We were still funding the business ourselves, so we thought it would be a really good opportunity to take on a partner who could fund the growth for the company. We didn't all agree. Katy, Andy, and I agreed. Pamela took us all aside and said, “No, once we do this, we don't own the company anymore. That's it. You give up control.” In our partnership with them, we still ran the business day-to-day. We would meet with them quarterly for board meetings, and it was pretty amicable for the most part. The only thing is, they weren't manufacturers, they were retailers. So they couldn't grasp that part of our business in a way that a strategic partner would have. So that got a little frustrating sometimes. They wanted us to pull back on some creative things that we wanted to do. They didn't understand why Andy did his films — I just remember one of the executives making a snide remark about it. And at the end of that meeting, we all walked out and we're like, Oh, boy, I hope that partnership survives.

Well it did and then Liz Claiborne came along and bought the brand outright for $124 million. But when you're writing about both of those deals in the book, you don’t provide the figures. Why not provide those details? Because anyone can look it up.

I don't want people thinking about what Pamela got, what Andy and Katy got, what I got. When you look up Katy and Andy, it looks like they own the entire thing, so it looks like they got all the money and they're worth this much. And it's not true. Several friends, financial guys were like, “You’ve got to put the money in there.” And I was like, “I don't really want to.”

I thought it was really humanizing the way you talked about Katy’s relationship to fame and how it just wasn’t for her. How does one reconcile that with her becoming a household name?

She got really good at [being a public figure] over time. The whole thing about becoming famous, I think, is you naturally become more insular because you want your private space and you want to be with your friends alone. So you stay at home more often. You have to look good every single time you walk out the door — there's always going to be somebody with a camera in their hands. She got really good at public speaking, but she still didn't love large groups of people

How many hours did you guys work in the beginning? What were your days like?

A lot. It never stopped. We talked all weekend on the phone. I was always there early, like 7 or 7:30. I grew up on a farm, so I'm an early riser anyway. But Katy and I would stay until nine or 10 at night because if our factory was working — they were right down the hall from us — we would go down and sit and talk with the guys in the factory. There was always stuff to do. And it was such an exciting time that I just didn't want to stop doing it.

When the four of you did part from the company after the Liz Claiborne acquisition, you portray Katy as being completely fine with letting it go and getting her time back. That’s sort of antithetical to how we think about people in fashion selling their brands and losing the rights to their names. For Halston, selling his name and losing that control was portrayed as his downfall.

Yeah. She never complained to me about it. Not once. It's funny, I'm sure on some level it did bother her, because she couldn't go do something else with her name. And then when we started Frances Valentine, we had to be very careful about using her as the person [behind it]. Once you sell your name, that's it.

You have an anecdote in the book about how an executive came in who wanted Kate Spade to sell a $1,200 python handbag, which you thought was too expensive and off-brand. Today we hear about crazy-expensive bags all the time. What do you make of the handbag market today?

Everybody's a handbag designer. All the luxury brands who did apparel first — they've all gone into accessories because there's no sizing and they're more profitable. So it's a tough market out there. We've kind of stuck with our same philosophy about it though. You want a really good functional bag that's stylish and cool at a good price point, and really good leather — we're still doing that.

And you acknowledge in the book that she was depressed towards the end of her life, but you don't go into detail about it. How did you suss out where that line was?

Katy was a very private person, and there was such a stigma about depression [when she died], and I think she felt it. So it wasn't something she wanted to discuss very much, but she was getting help. She'd have down days sometimes, and we talked about it. I've never had a day when I couldn't get out of bed, so I don't know what that feels like.

What would Katy have thought of your book?

Well, we probably would have planned to write it together and then never get around to it. I don't know. I'm sure she would find plenty of fault with it, but I hope she would like it.

You said in the beginning that you promised not to share her secrets. So, did you?

No, I didn't. Anything that she would never want me to tell, I would never tell.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.